Source: Sara Stathas for Wisconsin Watch

Deanna Branch thought she found the perfect home to rent on Milwaukee’s North Side: a two-story house with a balcony near her sons’ school, two grocery stores and a park.

Perfect until severe lead poisoning in 2015 sent Branch’s then-2-year-old son Aidan to Children’s Wisconsin hospital.

Her landlord replaced the home’s lead-painted windows but didn’t address remaining hazards, Branch said. After Aidan returned to the hospital three years later, state Child Protective Services said Aidan couldn’t leave unless she could provide a lead-free home, she recalled.

She broke her lease and immediately moved in with family and later lived at a shelter.

Her rental company management, Ogden and Company, Inc., sued Branch and garnished her mother’s wages for years, since she had co-signed on the lease, she said. The situation hardly seemed fair.

“I broke my lease, but you almost killed my son,” Branch said of her landlord. “So I figured we will be a little bit even.”

Branch has since become an advocate for parents facing lead hazards, even spotlighting the issue as a guest during President Joe Biden’s 2023 State of the Union address.

But her experience remains common in Milwaukee. More than half of city households rent — the highest percentage in the Midwest — and an estimated 200,000 aging housing units likely have paint made with lead, a neurotoxin that damages the brain and nervous system, especially in young children.

Through its News414 collaboration, Wisconsin Watch also spoke to Dennise Honegger, who moved between four lead-tainted Milwaukee-area rentals between 2017 and 2023, leading to hospital stays for her daughter and grandson, scrutiny from Child Protective Services and months of homelessness before finally finding a lead-free home.

Homeowners can make their properties safer by removing lead paint, dust or water pipelines, and some government programs subsidize that process. But renters, whose children disproportionately face lead risks, rely on landlords to take action. Landlords see few incentives to renovate on their own, and Milwaukee regulators — limited by a lack of funds and a state law that capped inspection fees on landlords — provide little oversight over lead-tainted rentals.

That reality reinforces deep racial and socioeconomic disparities in one of the nation’s most segregated cities.

Branch is co-founder of the Coalition on Lead Emergency, which educates renters about lead hazards and advocates for more oversight. The group hears from many families who struggle to respond after their children were poisoned in rentals, said Richard Diaz, another coalition co-founder.

Few tenants feel comfortable complaining about unaddressed lead hazards, and some who do may risk retaliation — whether through rent hikes or eviction, particularly in Milwaukee’s most lead-impacted neighborhoods, he said.

“You hear the same story, just time and time again,” Diaz said. “Kids lead poisoned, landlord doesn’t care, they get evicted.”

The Milwaukee Common Council sought to tackle this problem in July 2022, enacting an ordinance designed to prevent landlord retaliation and stiffen penalties for refusal to address detected lead. That included allowing the Milwaukee Department of Neighborhood Services (DNS) to allow tenants to withhold rent when landlords fail to comply.

But DNS received zero rent-withholding referrals during the first year of the ordinance, a spokesperson said.

DNS can refer lead-related complaints to the city health department for enforcement, but the agency says few complaints specifically mention lead. DNS often receives complaints about peeling paint, a common sign of lead hazards. But it has authority only over building codes and not the health codes that deal with lead hazards. So if a child isn’t yet found to be lead poisoned, DNS simply orders landlords to repaint without abating lead.

That risks further contaminating properties if a contractor scrapes away old paint without properly cleaning up, said Michael Mannan, the city health department’s director of home environmental health.

In those cases it’s up to landlords to act in good faith — to recognize they might have lead, test their properties and remediate if need be, DNS Commissioner Erica Roberts said.

The city health department issued just 26 citations to 13 companies or individual landlords for unaddressed lead problems from July 2022 to June 2023, with nine citations against four entities later dropped due to out-of-date inspections, according to public records obtained by Wisconsin Watch.

Four entities were deemed guilty of eight citations due to a failure to show up in court — with each citation carrying an $801 fine. Three entities had six citations dismissed because they responded and received funding for abatement, records show. Two citations against a company were returned as undeliverable.

Landlords sometimes refuse inspectors entry for fear they will find other code violations, Mannan said.

“We know it’s not working,” Mannan said about broad city efforts to rid rentals of lead. “We have to do something.”

To be sure, not all landlords are the same. They include mom-and-pop landlords who “just don’t have the resources to be able to abate properties,” Diaz said. The average cost of lead abatement is about $40,000 per unit, according to the Milwaukee Health Department.

Most landlords try their best to maintain their properties amid challenges with costly repairs and maintenance, said Chris Mokler, director of legislative affairs for the Wisconsin Real Estate Investors Association, which advocates for landlords and property investors.

“They don’t want any children infected. But again, they didn’t paint the property,” he said, arguing that health departments should focus more on incentives than punishments.

Mokler’s group years ago pushed for a statewide low interest loan program for landlords to cover lead abatement costs. The legislation never gained traction.

The state’s Lead-Safe Homes program covers 100% of abatement costs to landlords, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS). It has completed lead abatement in 332 homes statewide — 119 rentals and 213 occupied by owners — since its launch in 2020.

Like many parents, Branch didn’t learn about lead risks until a test showed her child was poisoned. She didn’t know how to react.

“I just felt like as a mother, I was definitely failing him because I didn’t know the answer,” Branch said.

Federal law requires landlords to inform tenants about lead paint in properties built before 1978. Branch doesn’t recall receiving such information when moving into her rental. Brittany Schoenick, an attorney with Legal Action of Wisconsin who represents renters in court, said she has frequently seen landlords flout the federal disclosure law.

A test through the state’s Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program showed about 40 micrograms of lead per deciliter in Aidan’s blood, Branch recalled. That was eight times the level the state defines as poisoning: 5 mcg/dL.

Living in an aging North Side Milwaukee rental, Aidan was among Wisconsinites most likely to face lead exposure. In 2022, Wisconsin’s Black children were four times more likely than white children to face lead poisoning, data show.

Childhood lead poisoning rates in Milwaukee and statewide have dipped in recent decades — in line with national trends since lead was phased out in paint and gasoline. But hazards still persist.

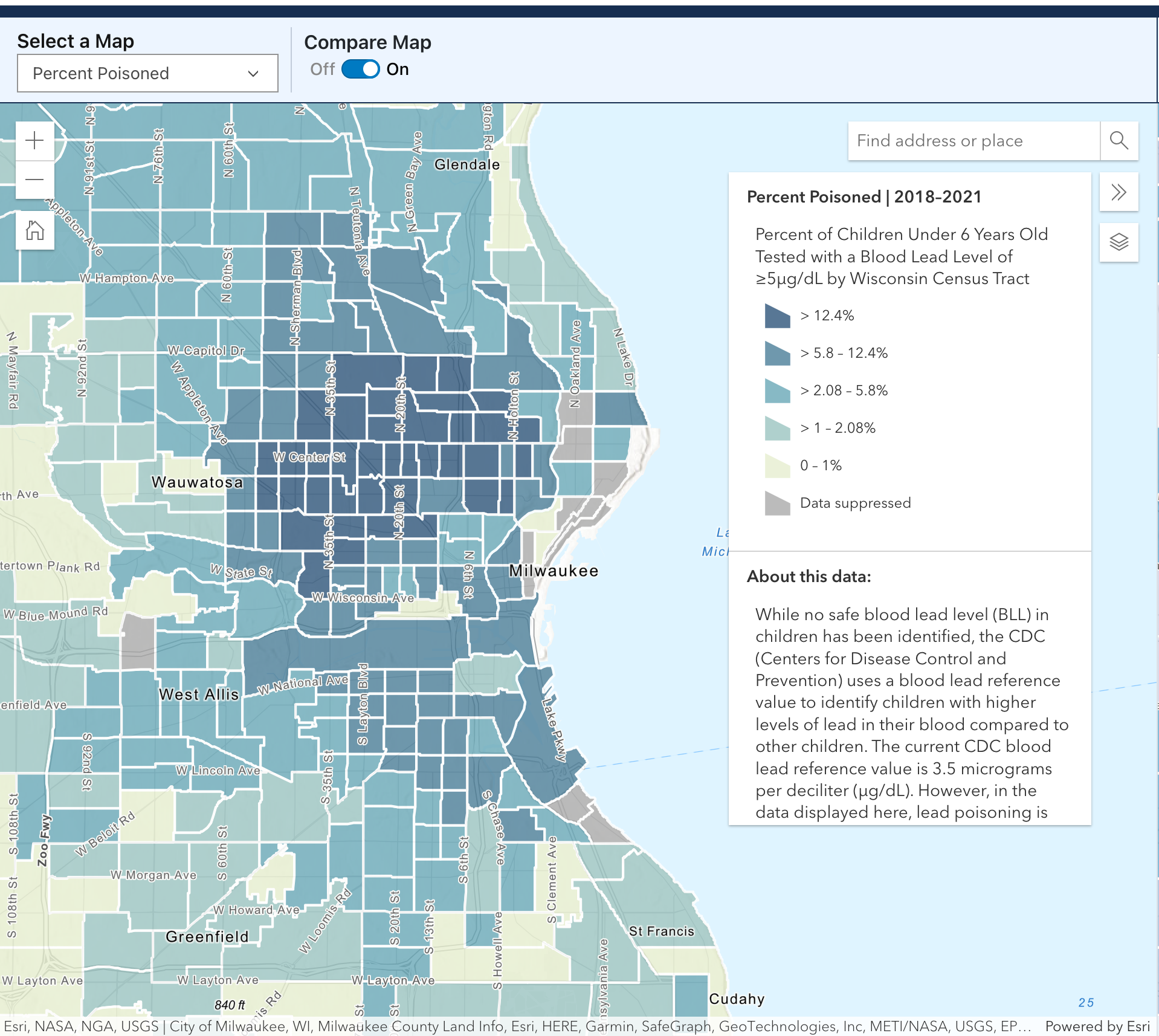

The majority of Wisconsin’s lead-poisoned young children live in Milwaukee County, where 4.7% of children under six tested in 2021 had blood lead levels above 5 mcg/dL. That’s compared to 2.8% of the young children tested statewide, according to DHS data. Those are just known cases. Testing decreased during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Testing data from 2018 to 2021 show childhood lead poisoning in some North Side Milwaukee census tracts ranging above 15% or even 20%.

Aidan’s initial level was high enough to send him to the hospital, and it seemed to explain his early behavioral issues.

The test also detected lead at twice the threshold for the city health department to require the landlord to fix the hazard (15 mcg/dL), with the city covering the costs.

But after the health department finished its inspection, officials weren’t initially sure where to send their report, Branch recalled: Four landlords had cycled through the property during Branch’s time as a tenant, she said. Milwaukee tenants say they commonly face such challenges in seeking accountability for lead poisoning, particularly with out-of-state landlords.

Branch’s landlord replaced the home’s window, but that didn’t stop Aidan’s exposure.

A 2018 health department test of the home found lead in deteriorating plaster and wood in the bedrooms, pantry, hallway and front porch.

Another blood test detected 50 mcg/dL in Aidan’s blood, sending him back to the hospital. That’s when CPS told Branch that Aidan couldn’t be discharged without a lead-free home, Branch said.

“I thought: ‘Oh my God. I’m going to lose my kids. I’m a terrible mother,” Branch recalled. “The people who were supposed to be helping me provide a safe place for my son — it felt like they were against me. They were blaming me for what happened to my son.”

Gina Paige, a Wisconsin Department of Children and Families spokesperson, said her agency does not track how often lead poisoning prompts CPS involvement. In such situations, the agency says, CPS may work with local health departments to aid families.

Medical professionals say it’s critical to immediately remove children from lead sources. But the waitlist for abatement is about a year long, Mannan said. In most cases, the local health department will vacuum up immediate hazards once a child is found to be poisoned. Waiting on full renovations can take much longer.

Branch said her landlord promised to fix all the lead hazards once she re-upped her lease for another year. She refused and broke her existing lease early — especially scared after CPS’ warning.

“I lost all trust in landlords. I lost all trust in this building,” she said. “And I’m not going to sign anything because I’m already hurting my son by being here.”

The move prompted Ogden and Company to sue, damaging Branch’s credit and siphoning her mother’s wages until the debt was paid. Branch said she didn’t learn of the lawsuit until landlords elsewhere denied her rental applications.

The family this year successfully petitioned the court to seal records from the lawsuit.

An Ogden and Company spokesperson declined to comment on the litigation and wrote in an email: “In most cases, we are a third party management firm for an ownership entity that we neither own nor control.”

Branch initially turned to extended family for housing and later moved into a shelter when she “became a burden to live with,” she said.

With funding scarce, the city health department offers few home relocation resources other than making referrals to other agencies. The home must be condemned for renters with written orders from DNS to receive such support. That might include 30 days of rent assistance from Community Advocates, a social services nonprofit, Mannan said.

That’s what Honegger, a retired nurse, discovered when she was forced to relocate when her daughter and grandson were exposed to lead in four Milwaukee rental properties. Doctors at one point found paint chips in the daughter’s stomach, causing her lead levels to skyrocket, Honegger said.

Honegger said she received a 30-day hotel voucher, but she paid out of pocket for the rest of the year and lost lead dust-covered possessions as she continued searching for a safe, affordable rental.

“We lost clothes, furniture, everything. We had to catch up with hospital bills,” Honegger said.

The health department said it’s working with philanthropy, hospital systems and foundations to expand funding for lead abatement and associated costs, Mannan said.

“We’ve already built a system,” Mannan said. “We just need you to help fund it. The taxpayers can’t fund it on their own.”

The city health department is taking a new approach with landlords. It ended a process in which a landlord would automatically qualify for a taxpayer-funded abatement when a child was found to be poisoned — and would be cited only when refusing to hire a contractor. However, low-income property owners can still receive subsidized abatement.

Under the new process, the city will charge re-inspection fees to unresponsive landlords as the first step in an escalated enforcement strategy for compliance. If a landlord doesn’t abate after two warnings, the city can continue reinspection fees at $350, issue citations, or ask a judge to allow the department to perform the work itself and add the costs to the landlord’s building taxes.

Still, those actions come only after a child is found to be poisoned. Renter advocates want the city to proactively investigate lead and other hazards.

Rochester, New York, and Cleveland, Ohio, are among cities that require inspections for lead hazards before tenants move in. Advocates say those ordinances could help curb childhood lead poisoning.

That’s not possible in Milwaukee due to the state law capping inspection fees, Mannan said. With so many suspect properties, the city could not afford proactive inspections without raising fees on landlords.

Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled Legislature capped fees as part of a series of laws that limited local renter protections. Beginning in 2011, lawmakers — including some who themselves are landlords — also prohibited municipalities from requiring rentals to be certified, registered or licensed and limited the scope of rental inspection programs.

The changes prompted Milwaukee in 2016 to shutter a DNS program that performed additional rental inspections in areas dense with rental properties.

The Wisconsin cities of Eau Claire, Racine and Oshkosh require rental inspections for certain building hazards, using careful wording to comply with the state’s narrowed law. State law allows targeted rental inspections to address “habitability” violations that pose a “substantial hazard to the health or safety of the tenant.” Cities can define that to include lead.

Eau Claire’s targeted inspections prompted two full lead inspections at properties in the last year, according to Matt Steinbach, the environmental sciences division manager for the Eau Claire City-County Health Department.

Roberts acknowledged that Milwaukee could legally target lead similarly, but said the city lacks funding to do so on a large scale.

Branch’s family now lives in a lead-free rental. Aidan, now 10, still faces challenges that Branch suspects relate to early lead exposure. He struggles to stay focused due to an attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis, and he can turn angry and argumentative — symptoms of his diagnosed oppositional defiant disorder.

But Branch has learned to better communicate with Aidan. He now helps take care of his little sister and enjoys drawing pictures — including for a children’s book Branch authored in which Aidan defeats the “evil lead monster.”

“It really is awesome to see how much he’s grown,” Branch said. “I never thought we would get there.”

As for Honegger, her 12-year-old daughter is enrolled in school special needs programs, and she said lead exposure did not help the behavioral issues of her four-year-old grandson who is on the autism spectrum.

But Honegger was relieved in June to sign a lease at a lead-free rental.

“There is not one speck of lead in my house now. I am so happy,” Honegger said. “I got tears in my eyes.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Civic Media Inc.

Put us in your pocket.

4201 Victory Ave. Racine, WI 53405

Studio: (262) 300-7445 (text or call)

Office: (262) 634-3311