Source: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch

Wisconsin’s ‘death grip with alcohol’ is killing more residents

Excessive alcohol use is taking a heavy toll in a state that celebrates its drinking culture.

Blanketing the wall of an American-style dive bar in Prague: the Milwaukee Brewers, the Tavern League of Wisconsin and the iconic phrase “Drink Wisconsibly.”

Not only does Wisconsin consistently rank among the U.S. states with the highest excessive drinking rates, its high alcohol consumption draws global recognition.

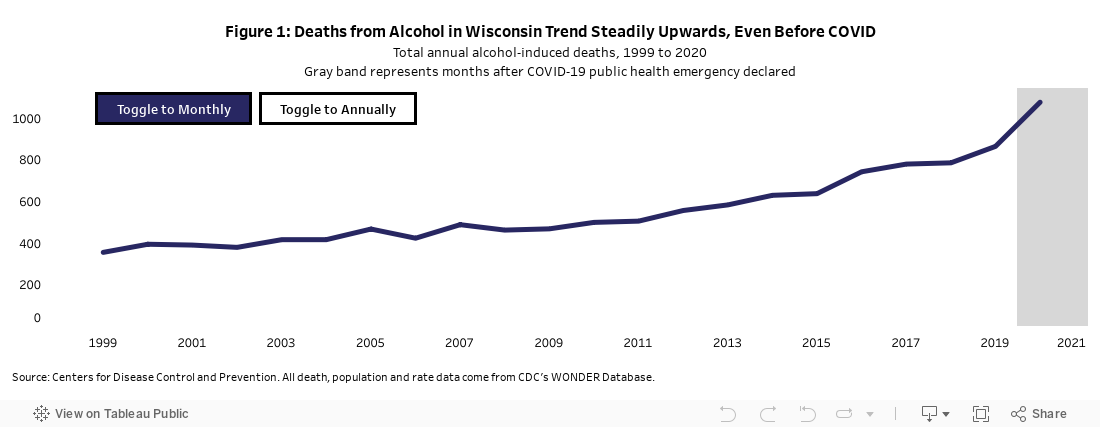

While many Wisconsinites take pride in this reputation, alcohol is taking lives at unprecedented rates in the state.

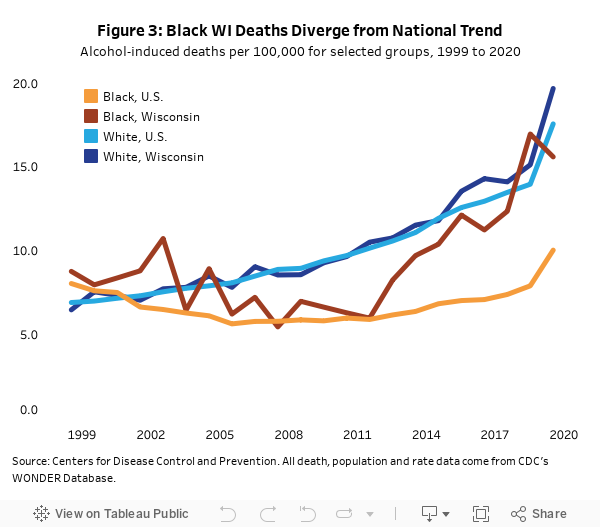

In 2020, Wisconsinites died from alcohol-induced causes at a rate nearly 25% higher than the national rate. The rate tripled from 6.7 to 18.5 per 100,000 from 1999 to 2020.

Wisconsin is “locked in this weird death grip with alcohol,” said John Eich, director of the Wisconsin Office of Rural Health. “There’s a cultural level of acceptance of excessive drinking.”

Despite challenges, some are pushing back against permissive drinking laws and culture.

After a drunk driver killed her son in 2018, Sheila Lockwood started lobbying to reform laws in Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin.

“I don’t know what else to do with the pain other than trying to change something,” Lockwood said. “If I can help somebody from going through this, then you just turn your pain into some sort of change.”

Binge drinking inflicts most harm

About 65% of Wisconsin’s adults reported having at least one drink over the previous 30 days — far above the 55% national estimate, according to 2019 federal survey data.

But binge drinking inflicts most alcohol-related harm, said Maureen Busalacchi, director of the Wisconsin Alcohol Policy Project, part of the Comprehensive Injury Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Binge drinking consists of four to five alcohol servings over two hours. Any alcohol consumed by underaged and pregnant people is excessive, and heavy drinking involves one to two drinks daily, Busalacchi said.

“While it doesn’t sound like a lot, it definitely raises your risk for all kinds of issues, including cancer, and if you need to drink every day, you probably should talk to somebody,” Busalacchi said.

About one-third of Wisconsin adults in 2019 reported binge drinking in the previous month, more than any state except for North Dakota.

That thirst has proved deadly.

Wisconsin experienced 1,077 alcohol-induced deaths in 2020, up from 865 in 2019, a Wisconsin Policy Forum report found. The tally included deaths from poisoning and certain liver, digestive and neurological diseases. It excluded accidents, falls, cancers and suicide. The nearly 25% increase was the biggest one-year jump in two decades.

Alcohol death trends predated pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic may have fueled the deadly trend, as people already facing an alcohol use disorder stayed home and drank more, Busalacchi suggested.

“Maybe health care wasn’t accessible. We’re not sure of all the reasons,” she said.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1690573502333’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; vizElement.style.width=’1100px’;vizElement.style.height=’427px’; var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

But alcohol killed a growing number of Wisconsinites even before the pandemic. From 2000 to 2010, statewide alcohol-induced deaths increased by nearly 27% before more than doubling over the next decade. Nearly two-thirds of the 2010-to-2020 surge predated the pandemic, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

All age groups experienced more alcohol-induced deaths over the time period.

Meanwhile, liver disease has increasingly affected younger people, particularly women.

“Normally that was a disease in your 50s and 60s, but we’re seeing it in women in their 30s because of the high-intensity drinking,” Busalacchi said.

The Wisconsin Policy Forum report highlighted racial disparities in deaths. The alcohol-related death rate for Black Wisconsinites has surged in the last decade. Despite a slight reduction in 2020, the death rate of 15.6 per 100,000 remained among the highest nationwide. American Indian or Alaska Natives in Wisconsin died at a far higher rate than any other race in 2020: 66 per 100,000 people.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1690573573312’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; vizElement.style.width=’600px’;vizElement.style.height=’527px’; var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

Those figures exclude motor vehicle accidents, where alcohol can factor heavily.

While Wisconsin has seen a long-term decline in deaths related to drunk driving, a separate Wisconsin Policy Forum report found a near 50% increase — from 52 to 78 — in alcohol-involved crash fatalities during the study period in 2020, relative to 2019. More impaired and reckless driving during the pandemic helped drive the trend, researchers said.

As of May 1, alcohol was involved in at least 10 of 16 fatal snowmobile crashes in 2023, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

County health departments typically rank alcohol abuse in their top three priorities, Busalacchi said. But initiatives to address the problem remain underfunded.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services lacks designated alcohol subject matter experts, says Maggie Northrop, the agency’s Healthy Wisconsin coordinator.

“In Wisconsin, we seem to give up and chuckle at those drunks,” said Eich of the state Office of Rural Health.

Fury over drunk driving fuels action

The advocacy nonprofit Mothers Against Drunk Driving wants Wisconsin to join 45 other states in a Driver License Compact — helping states exchange data related to license suspensions and traffic violations. Wisconsin’s lack of membership may allow people who drive drunk outside of their home state to face fewer consequences.

In 2018, Austin Lockwood, 23, was riding in the passenger seat of Eric Labahn’s Chevy Trailblazer in Three Lakes, Wisconsin, where Lockwood was helping Labahn, an Illinois resident, clean a cabin.

Labahn, who had just turned 21, told police he swerved to avoid a deer before smashing into a tree, killing Lockwood.

Labahn survived and refused a blood test at the scene, according to media reports. A test hours later showed a blood alcohol concentration of .117, well above the legal limit of .08.

Labahn faced charges in Wisconsin of homicide by intoxicated use of a vehicle but kept legally driving for a year and a half after the crash.

Since Wisconsin is not in the Driver’s License Compact, Illinois officials were not alerted of the crash and did not suspend his license.

Labahn surrendered his Illinois license several months later and moved to Wisconsin, which granted him a license, allowing him to drive legally while the case was still pending.

Wisconsin law requires a one-year license suspension for drivers who refuse a blood alcohol test, but it gave Labahn the right to a hearing on the suspension — and to keep his license ahead of that hearing, which faced delays tied to the homicide case.

“It’s infuriating,” Sheila Lockwood said. “He had no consequences for a year and a half. He went out and partied. He went to Cubs games. He was celebrating his college graduation. And our lives are literally destroyed.”

In October 2019, the driver Eric Labahn was sentenced to three years of initial prison confinement with four additional years of extended supervision. Lockwood believes her efforts to raise awareness — yielding more than 80 victim impact letters sent to the judge — led to the steeper penalty than what the state recommended.

A month later, Lockwood joined Gov. Tony Evers as he signed Wisconsin Act 31, establishing a mandatory minimum five-year sentence for those convicted of homicide by intoxicated use of a vehicle. The law allows shorter terms “if the court finds a compelling reason and places its reason on the record.”

Lockwood pushed for a heavier penalty against Labahn. “But nothing would ever be enough. Because it’ll never bring Austin back.”

Little traction on the state level

Wisconsin remains a national outlier in its lax penalties for intoxicated driving — particularly for first and second-time offenders.

While most states classify a first Operating While Intoxicated charge as a misdemeanor, for instance, Wisconsin considers it a non-criminal charge without jail or prison penalty. First-time offenders in Wisconsin typically face a fine and a driver’s license revocation for six to nine months.

The state requires interlocking devices for drivers who refuse to take breathalyzer tests at traffic stops and all repeat offenders. The requirements don’t extend to first-time convicted drivers unless their blood alcohol concentration measures .15 or higher.

When ignition interlocks are installed, drivers must blow into the mouthpiece, allowing a device to measure their breath alcohol content. The vehicle will not start if the driver’s alcohol content is above 0.02%, below the 0.08% legal limit for blood alcohol concentration.

Interlocks reduce repeat drunk driving offenses by about 70% while installed, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mothers Against Drunk Driving has spent years urging Wisconsin lawmakers to extend interlock mandates to all first-time offenders and join 34 states and the District of Columbia that require them for all people convicted of drunk driving.

Evers, a Democrat, proposed such a change in his 2023-25 budget. The Legislature’s Republican-controlled Joint Committee on Finance removed the provision along with hundreds of others before Evers ultimately signed the budget in July.

Most alcoholism goes untreated

For those seeking help with alcohol addiction? Wisconsin has a shortage of treatment providers, and high costs further limit options, said Busalacchi of the Wisconsin Alcohol Policy Project.

An estimated 80% of Americans with an alcohol use disorder never receive treatment, and 14% of those who don’t seek help cite cost as a barrier, a Recovery Research Institute study found. The most common reason for avoiding treatment: The thinking that “I should be strong enough to handle it on my own.”

The Department of Health Services in February released a state health improvement plan focused on building community-based solutions rather than an individualistic approach. It includes addressing issues that fall outside of the typical domain of public health agencies, such as access to housing, childcare and other resources. Busalacchi said a community approach could help tackle Wisconsin’s alcohol problems.

Seeking solutions

An example is Operation River Watch, formed to monitor Riverside Park in La Crosse after eight college students between 1997 and 2006 were found to have drowned in the Mississippi River after excessive drinking. Volunteers have prevented further drownings by making sure people don’t enter the park at late hours on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights.

The CDC’s community-based recommendations to reduce alcohol consumption include taxing alcohol, limiting the density of alcohol outlets through zoning or licensing policies, using liability laws to prevent sales to underage people and limiting liquor store hours.

Focusing solely on individuals rather than communities won’t address the full scope of Wisconsin’s alcohol problem, Busalacchi said.

“Population-level approaches work best versus only doing individual things,” she said. “You kind of have to do both, right?”

Wisconsin Watch’s Rachel Hale contributed reporting to this story.

Find treatment for alcohol addiction in Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services sponsors a Wisconsin Addiction Recovery Helpline, which offers free, confidential, statewide resources for finding substance abuse treatment and recovery services. Call 2-1-1 or visit 211wisconsin.communityos.org/ for more information.

A Mental Health America of Wisconsin searchable database can be filtered to show resources related to drug and alcohol recovery.

A searchable Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration resources database can be filtered by type of service, payment options and treatment options.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Jimmie is Civic Media’s Sports Director who also works in digital content, sports, news, and talk programming. Email him at [email protected].

Want More Local News?

Civic Media

Civic Media Inc.

The Civic Media App

Put us in your pocket.